|

| BGS Image ID: P241716 |

|

| BGS Image ID: P241720 |

|

| BGS Image ID: P241717 |

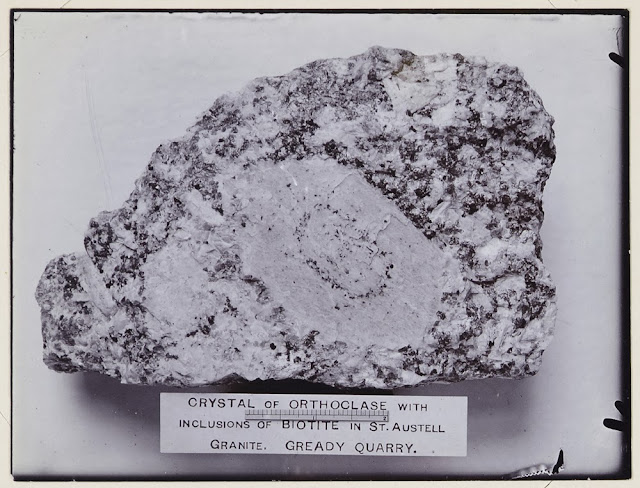

A series of photographs taken by R.H. Preston illustrating weathering of granite. The photographs were donated to the British Association for the Advancement of Science Collection. Photographs are dated 1895.

See also 'The Drum Rock'

Posted by Bob McIntosh